1

The Herd

The wind was blowing out of the east, which made the beast uneasy. It wasn’t normal. And anything that wasn’t normal made him uneasy. A stray sound. A flutter of a branch. The wind coming from the east.

But there was a scent on this wind. A familiar scent. One embedded in the big stallion’s being for millions of years. He spun on his heels and sure enough, there it was, easily within sight, apparently not realizing the wind had shifted. The stallion screamed to the matriarch who wheeled in flight.

Like one, the herd followed, racing away at lightning speed, the great stallion bringing up the rear. They ran without looking back for just over a quarter of a mile before the leader slowed and turned.

The predator, a small female cougar, had tired. She had been betrayed by the east wind. The horses had gotten away early, and now she was turning back.

The stallion’s senses had saved them this time. The entire herd was alive and well because those very senses had helped their ancestors survive for some fifty-five million years. Prey, not predator, the horse must suspect everything. Every movement. Every animal. Every smell. Every shadow. All are predators until proven innocent. By taking flight, not staying to fight, they survive.

And by staying together. Always together.

How well the big stallion knew this. He had watched his mother, in her old age, lose this very special sense and drift away from the herd. It was excruciating. His responsibility was the herd. To keep them together, and moving. But his mother’s screams in the distance would live with him forever.

The matriarch began to lick and chew, a sign that she was relaxing, that all was well. The stallion took her signal, and one by one, the herd began to graze again, nipping at the random patches of grass and the occasional weed. But they wouldn’t stay long. The matriarch would see to it. She would move them almost fifteen miles this day foraging for food and water, staying ahead of wolves and cougars. And keeping themselves fit and healthy.

2

The Student

I remember that it was an unusually chilly day for late May, because I recall the jacket I was wearing. Not so much the jacket, I suppose, as the collar. The hairs on the back of my neck were standing at full attention, and the collar was scratching at them.

There was no one else around. Just me and this eleven-hundred pound creature I had only met once before. And today he was passing out no clues as to how he felt about that earlier meeting, or about me. His stare was without emotion. Empty. Scary to one who was taking his very first step into the world of horses.

If he chose to do so this beast could take me out with no effort whatsoever. He was less than fifteen feet away. No halter, no line. We were surrounded by a round pen a mere fifty feet in diameter. No place to hide. Not that he was mean. At least I had been told that he wasn’t. But I had also been told that anything is possible with a horse. He’s a prey animal, they had said. A freaky flight animal that can flip from quiet and thoughtful to wild and reactive in a single heartbeat. Accidents happen.

I knew very little about this horse, and none of it firsthand. Logic said do not depend upon hearsay. Be sure. There’s nothing like firsthand knowledge. But all I knew was what I could see. He was big.

The sales slip stated that he was unregistered. And his name was Cash.

But there was something about him. A kindness in his eyes that betrayed the vacant expression. And sometimes he would cock his head as if he were asking a question. I wanted him to be more than chattel. I wanted a relationship with this horse. I wanted to begin at the beginning, as Monty Roberts had prescribed. Start with a blank sheet of paper, then fill it in.

Together.

I’m not a gambler. Certainty is my mantra. Knowledge over luck. But on this day I was gambling.

I had never done this before.

I knew dogs.

I did not know horses.

And I was going to ask this one to do something he had probably never been asked to do in his lifetime. To make a choice. Which made me all the more nervous. What if it didn’t work?

What if his choice was not me?

I was in that round pen because a few weeks earlier my wife, Kathleen, had pushed me out of bed one morning and instructed me to get dressed and get in the car.

“Where are we going?” I asked several times.

“You’ll see.”

Being the paranoid, suspicious type, whenever my birthday gets close, the ears go up and twist in the wind.

The brain shuffled and dealt. Nothing came up.

We drove down the hill and soon Kathleen was whipping in at a sign for the local animal shelter.

Another dog? I wondered. We have four. Four’s enough.

She drove right past the next turn for the animal shelter and pulled into a park. There were a few picnic tables scattered about. And a big horse trailer.

The car jerked to a stop and Kathleen looked at me and smiled. “Happy birthday,” she said.

“What?” I said. “What??”

“You said we should go for a trail ride sometime.” She grinned. “Sometime is today.”

Two weeks later we owned three horses.

We should’ve named them Impulsive, Compulsive, and Obsessive.

Our house is way out in the country and it came with a couple of horse stalls, both painted a crisp white, one of them covered with a rusty red roof. They were cute. Often, over the three years we had lived there, we could be found in the late afternoon sitting on our front porch, looking out over the stalls, watching the sun sink beneath the ridge of mountains to the west. One of us would say “Those stalls surely seem empty.” Or, “Wouldn’t it be nice if there were a couple of horses ambling back and forth down in the stalls?”

Like a postcard.

A lovely picture at sunset.

With cute horse stalls.

Lesson #1: Cute horse stalls are not adequate reason to purchase three horses.

Never mind the six we own now.

We had no idea what we were getting into. Thank God for a chance meeting with Monty Roberts. Well, not a real meeting. We were making the obligatory trip that new horse owners must make to Boot Barn when Kathleen picked up a California Horse Trader. As we sat around a table watching the kids chomp cheese burgers, she read an article about Monty and passed it over to me. That’s how I came to find myself in a round pen that day staring off our big new Arabian.

Monty is an amazing man, with an incredible story. His book The Man Who Listens to Horses has sold something like five and a half million copies and was on the New York Times best-seller list for 58 weeks! You might know him as the man who inspired Robert Redford’s The Horse Whisperer. I ordered his book and a DVD of one of his Join-Up demonstrations the minute I got home, and was completely blown away. In the video, he took a horse that had never had as much as a halter on him, never mind a saddle or rider, and in thirty minutes caused that horse to choose to be with him, to accept a saddle, and a rider, all with no violence, pain, or even stress to the horse!

Thirty minutes!

It takes “traditional” horse trainers weeks to get to that point, the ones who still tie horses legs together and crash them to the ground, then spend days upon days scaring the devil out of them, proving to the horse that humans are, in fact, the predators he’s always thought we were. They usually get there, these traditional trainers, but it’s by force, and submission, and fear. Not trust, or respect.

Or choice.

In retrospect, for me, the overwhelming key to what I saw Monty do in thirty minutes, is the fact that the horse made the decision, the choice. The horse chose Monty as a herd member and leader. And from that point on, everything was built on trust, not force. And what a difference that makes.

And it was simple.

Not rocket science.

I watched the DVD twice and was off to the round pen.

It changed my life forever.

This man is responsible for us beginning our relationship with horses as it should begin, and propelling us onto a journey of discovery into a truly enigmatic world. A world that has reminded me that you cannot, in fact, tell a book by its cover; that no “expert” should ever be beyond question just because somebody somewhere has given him or her such a label. That everybody and everything is up for study. That logic and good sense still provide the most reasonable answers, and still, given exposure, will prevail.

My first encounter with this lesson was way back when I was making the original Benji movie, our very first motion picture.

On a trip from Dallas to Hollywood to interview film labs and make a decision about which one to use, I discovered that intelligent, conscientious, hardworking people can sometimes make really big mistakes because they don’t ask enough questions, or they take something for granted, or, in some cases, they just want to take the easiest way. In this case it was about how our film was to be finished in the lab, and my research had told me that a particular method (we’ll call it Method B) was the best way to go. Everyone at every lab I visited, without exception, said, Oh no, no. Method A is the best way. When asked why, to a person, they all said Because that’s the way it’s always been done! In other words, don’t rock the boat.

Not good enough, says I. My research shows that Method B will produce a better finished product, and that’s what we want.

Finally, the manager of one of the smaller labs I visited scratched his head and said, “Well, I guess that’s why David Lean uses Method B.”

I almost fell out of my chair. For you youngsters, David Lean was the director of such epic motion pictures as Dr. Zhvivago and Lawrence of Arabia. I had my answer. And, finally, I knew I wasn’t crazy.

It’s still a mystery to me how people can ignore what seems so obvious, so logical, simply because it would mean change. Even though the change is for the better. I say look forward to the opportunity to learn something new. Relish and devour knowledge with gusto. Always be reaching for the best possible way to do things. It keeps you alive, and healthy, and happy. And makes for a better world.

Just because something has always been done a certain way does not necessarily mean it’s the best way, or the correct way, or the healthiest way for your horse, or your relationship with your horse, or your life. Especially if, after asking a few questions, the traditional way defies logic and good sense, and falls short on compassion and respect.

The truth is too many horse owners are shortening their horses’ lives, degrading their health, and limiting their happiness by the way they keep and care for them. But it doesn’t have to be that way. Information is king. Gather it from every source, make comparisons, and evaluate results. And don’t take just one opinion as gospel. Not mine or anyone else’s. Soon you’ll not only feel better about what you’re doing, you’ll do it better. And the journey will be fascinating.

We were only a year and a half into this voyage with horses as these words found their way into the computer, but it was an obsessive, compulsive year and a half, and the wonderful thing about being a newcomer is that you start with a clean plate. No baggage. No preconceptions. No musts. Just a desire to learn what’s best for our horses, and our relationship with them. And a determination to use logic and knowledge wherever found, even if it means exposing a few myths about what does, in fact, produce the best results. In short, I’ll go with Method B every time.

Cash was pawing the ground now, wondering, I suspect, why I was just standing there in the round pen doing nothing. The truth is I was reluctant to start the process. Nervous. Rejection is not one of my favorite concepts. Once started, I would soon be asking him to make his choice. What if he said no? Is that it? Is it over? Does he go back to his previous owner?

I have often felt vulnerable during my sixty-eight years, but rarely this vulnerable. I really wanted this horse to choose me.

What if I screw it up? Maybe I won’t do it right. It’s my first time. What if he runs over me? Actually, that was the lowest on my list of concerns because Monty’s Join-Up process is built on the language of the horse, and the fact that the raw horse inherently perceives humans as predators. Their response is flight, not fight. It’s as automatic as breathing.

Bite the bullet, Joe, I kept telling myself. Give him the choice.

I had vowed that this would be our path. We would begin our relationship with every horse in this manner. Our way to true horsemanship, which, as I would come to understand, was not about how well you ride, or how many trophies you win, or how fast your horse runs, or how high he or she jumps.

I squared my shoulders, stood tall, looked this almost sixteen hands of horse straight in the eye, appearing as much like a predator as I could muster, and tossed one end of a soft long-line into the air behind him, and off he went at full gallop around the round pen. Just like Monty said he would.

Flight.

I kept my eyes on his eyes, just as a predator would. Cash would run for roughly a quarter of a mile, just as horses do in the wild, before he would offer his first signal. Did he actually think I was a predator, or did he know he was being tested? I believe it’s somewhere in between, a sort of leveling of the playing field. A starting from scratch with something he knows ever so well. Predators and flight. A simulation, if you will. Certainly he was into it. His eyes were wide, his nostrils flared. At the very least he wasn’t sure about me, and those fifty-five million years of genetics were telling him to flee.

It was those same genetics that caused him to offer the first signal. His inside ear turned and locked on me, again as Monty had predicted. He had run the quarter of a mile that usually preserves him from most predators; and I was still there, but not really seeming very predatory. So now, instead of pure reactive flight, he was getting curious. Beginning to think about it. Maybe he was even a bit confused. Horses have two nearly separate brains. Some say one is the reactive brain and the other is the thinking brain. Whether or not that’s true physiologically, emotionally it’s a good analogy. When they’re operating from the reactive side, the rule of thumb is to stand clear until you can get them thinking. Cash was now shifting. He was beginning to think. Hmm, maybe this human is not a predator after all. I’ll just keep an ear out for a bit. See what happens.

Meanwhile, my eyes were still on his eyes, my shoulders square, and I was still tossing the line behind him.

Before long, he began to lick and chew. Signal number two. I think maybe it’s safe to relax. I think, just maybe, this guy’s okay. I mean, if he really wanted to hurt me, he’s had plenty of time, right?

And, of course, he was right. But, still, I kept up the pressure. Kept him running. Waiting for the next signal.

It came quickly. He lowered his head, almost to the ground, and began to narrow the circle. Signal number three. I’ll look submissive, try to get closer, see what happens. I think this guy might be a good leader. We should discuss it.

He was still loping, but slower now. Definitely wanting to negotiate. That’s when I was supposed to take my eyes off him, turn away, and lower my head and shoulders. No longer predatorial, but assuming a submissive stance of my own, saying Okay, if it’s your desire, come on in. I’m not going to hurt you. But the choice is yours.

The moment of truth. Would he in fact do that? Would he make the decision, totally on his own, to come to me? I took a deep breath, and turned away.

He came to a halt and stood somewhere behind me.

The seconds seemed like hours.

“Don’t look back,” Monty had warned. “Just stare at the ground.”

A tiny spider was crawling across my new Boot Barn boot. The collar of my jacket was tickling the hairs on the back of my neck. And my heart was pounding. Then a puff of warm, moist air brushed my ear. My heart skipped a beat. He was really close. Then I felt his nose on my shoulder… the moment of Join-Up. I couldn’t believe it. Tears came out of nowhere and streamed down my cheeks. I had spoken to him in his own language, and he had listened… and he had chosen to be with me. He had said I trust you.

I turned and rubbed him on the face, then walked off across the pen. Cash followed, right off my shoulder, wherever I went.

Such a rush I haven’t often felt.

And what a difference it has made as this newcomer has stumbled his way through the learning process. Cash has never stopped trying, never stopped listening, never stopped giving.

I was no longer a horse owner. I was a friend, a partner. A leader. And I promised him that day that he would have the very best life that I could possibly provide. There was only one problem. I didn’t have the vaguest idea what that was.

3

The Language

The big palomino stallion was anxious to leave, but the matriarch of the herd was scolding a young colt. And the time it took must be honored, the discipline performed, or the colt would grow up a selfish renegade, of no use to the herd, and would most likely wind up prey to a cougar or a wolf.

After the earlier run, the colt had been feeling his oats, adrenaline and testosterone pumping, and he had snapped and kicked at a couple of foals half his age. Not really meaning any harm, but it was unacceptable and dangerous behavior in the herd and had to be dealt with. The mare had squared up on him, her back rigid, ears pinned, and her eyes squarely on his. He knew exactly what she meant, and he now stood alone, well away from the herd. Alone was the scariest place for a herd member to be. Without the protection of the herd a pack of wolves could easily have their way with him. Before he would be allowed to return, however, he would have to demonstrate his penitence and the mare would eventually swing her back to him and relax, saying the apologies were accepted and he could rejoin the group.

The dominant mare, the matriarch, is the leader of the herd. Usually one of the more mature horses in the group, she serves as disciplinarian, dictates when and where the herd will travel, has the right to drink first from watering holes, and always claims the best grazing. The stallion is the guardian and protector. And the sire of every foal.

The great palomino was taking this quiet opportunity to wander through the herd and check his subjects after the run. It had surely been good exercise, and a sniff here and a look there confirmed for him that there had been no injuries. The steep rocky terrain had conditioned their hooves and legs into appendages of steel. Their daily movement kept the blood flowing and the muscles toned. They were indeed a hearty bunch. But they had to be, for being so was their only defense.

The stallion scanned the horizon, turning a full circle. The sun was low in the west and sometimes caused objects to become mere dark shapes against the light, difficult to distinguish one from another. But one particular shape on a distant ridge stopped him. It hadn’t moved, but didn’t really look like a rock, or a plant. He sniffed the air, but the wind was still coming from the east, and there was no scent other than the sweet smell of Indian paintbrush on the hillside.

The stallion waited. And his patience paid off. The dark shape moved. Turned. His heart began to pump and his nostrils flared. The most feared predator of all! More dangerous because he came astride one of their own, on a horse, capable of running as fast and as far as the herd itself could run. It was a man!

Over the past year, only two herd members had been lost to cougars or wolves, but five had been lost to man. All emblazoned upon the stallion’s memory. Long withering chases ending in herd members being slung to the ground, legs tied, whipped and dragged around until there was simply no fight left in them, their bodies and their beings stripped of strength and dignity.

The stallion slid up next to the matriarch, adding his burning stare to hers. Saying to the young colt: Now! The recalcitrant colt began to lick and chew, and he lowered his head. The two leaders turned their backs, allowing him to return. The matriarch had also seen the figure on the ridge. She uttered a low guttural call to the herd. She must now determine which way to lead them. Certainly not back toward the cougar. Her instincts told her to go south.

She glanced back at the western ridge. The dark shape was gone. There was no time to waste.

4

The Plot

How did we get here? How is it that we have taken this majestic animal which is fully capable of keeping himself in superb condition and living a long, healthy, happy life, and turned him into a beast of convenience, trained by pain and fear, cooped up in a small stall most of the time, subjected to a host of diseases caused, in most cases, by us.

One would think that the long history of the horse’s value to man, as beast of burden, draft animal, riding animal, and companion would have stirred such a thorough knowledge of his needs that he would have a better, healthier, longer life in our care than he ever could have in the wild. But, in most cases, the exact opposite is true.

According to Dr. Hiltrud Strasser, noted veterinarian, researcher, and author, horses in the care of man have a life expectancy that is, for the most part, only a fraction of that of their wild-living counterparts. Usually because of problems with their locomotor organs. In other words, lameness.

Issues with their feet.

Caused by wearing metal shoes. And standing around all day in a tiny box stall.

Is that a surprise? It was to me. A big one. And it propelled me onto a journey of discovery that quite simply upended everything I thought I knew, and virtually everything I was being told by the experienced and the qualified.

What I discovered was that most humans who own horses have no idea about what’s at stake—or what the alternatives are. They’re just doing what they’ve been told to do with no concept that they are causing emotional and physical stresses that depress and break down their horse’s immune system, cause illness and disease, and shorten life. And, in so many instances, prevents any kind of real relationship between horse and man.

Dr. Strasser is emphatic that, no matter what you’ve heard to the contrary, the horse living in the Ice Age, the present-day wild horse, and the high-performance domestic breeds of today are all anatomically, physiologically, and psychologically alike. They all share the same biological requirements for health, long life, and soundness. In other words, we could not only be making the horse’s life as good as it is in the wild, we could be making it better. At least as healthy. And happier!

Why aren’t we?

And what can be done about it?

Finding answers to these questions became the mission. The discoveries were mind boggling. The solutions remarkably uncomplicated, more often than not involving little more than a willingness to change. A willingness that, bewilderingly, all too often, wasn’t going to happen.

Leaning on the fence next to me, elbows propped on the top rail, was a true cowboy. Gnarled and weathered, crusty as they come, and a likable sort. Full of tales and experiences. He must’ve been near my age and had been riding since he was old enough to hold on. I actually paused long enough to absorb the moment, me with my Boot Barn boots and new straw hat, right there in the thick of it. Me and him. Cowboys.

Then he spoke for only the third time since Mariah had come out of her stall, and the reverence I was feeling cracked and shattered like the coyote in a Roadrunner cartoon.

Mariah was a cute little Arabian mare that the cowboy had for sale. Kathleen and I were still looking for the right horse for her. The cowboy had watched me earlier in Mariah’s stall, just hanging out, waiting for her to tell me it was okay to put on the halter. She never did. The cowboy had asked, “Do you want me to catch her?”

It made me uneasy, but I said, “No thanks.” It was that thing about choice again. Trying not to seem so much like a predator by racing into the stall and slapping the halter on first thing, horse willing or not. But I couldn’t push away the feeling of embarrassment. Even incompetence. As if I were being challenged. I knew I could corner her and catch her. The stall wasn’t that big. But I was attempting to stir some sort of relationship. Not my will over hers, like it or not. Finally I took her willingness to just stand still as an offer, and I slipped the halter over her head. She made no move to help. I rubbed her forehead. Then her shoulders, belly, hips, and again her face. She twitched, and pulled away, showing no warmth whatsoever.

I led her into the cowboy’s arena and turned her loose. It was a small arena, but too large for a real Monty Roberts kind of Join-Up. Still, I had to try. I wanted to see if I could break through the iciness. When I unsnapped the lead, she took off like I was the devil himself, galloping full stride around and around and around. For the most part, I was just stood there, doing nothing, mouth agape.

After several minutes, the cowboy asked again, “Do you want me to catch her?”

“No, it’s okay,” I mumbled, feeling like I was the one on trial, not Mariah.

And she continued to run. I made a couple of token tosses of the lead line, but they were quite unnecessary. She ran on for a good seven or eight minutes with no apparent intention of stopping. I was getting dizzy. Finally I quit circling with her, turned my back to the biggest part of the arena, dropped my shoulders, and just stared at the ground.

And on she ran. Around and around. I felt the cowboy’s eyes on me, probably saying: What kind of an idiot are you? Get a grip and catch the horse!

I was running out of will. But Mariah wasn’t running out of gas. I was ready to give up when quite suddenly she jolted to a halt. Just like that. Maybe ten or fifteen feet behind where I was standing. I just stood there, staring at the ground. After a moment or two, she took a few steps toward me, then a few more. Monty’s advice notwithstanding, I was peeking.

She never did touch me, but she did get within a couple of feet and just stood there. Finally I turned to her, rubbed her forehead, and snapped on the lead rope. I wanted to feel pleased, but didn’t. It was willingness without emotion. Her eyes were empty. Like an old prostitute. I know the gig. Let’s get on with it.

The cowboy then climbed aboard to demonstrate Mariah’s skills. I suspect he was on his best behavior. He didn’t appear to be particularly hard on her, but I noticed that his spurs seemed about two feet long and he did use them. She performed cleanly.

Then it was my turn in the saddle. Mariah pretty much did whatever I asked, but all the while, her lips were pouty and her ears were at half mast. Neither fish nor fowl. Not really showing any attitude, good or bad. Simply not into it. Not caring, one way or another.

Kathleen was next, woman to woman.

That’s when I walked back through the gate and propped myself on the fence-rail with the cowboy. And that’s when he said, “I’ve seen some of that natural horse pucky on RFD-TV and I’ve gotta tell you, the way I look at it that horse out there is here for one reason. My pleasure. And I’m gonna make sure she damn well understands that.”

I think she did. And, now, so did I.

Clinician Ray Hunt opens every clinic or symposium the same way. “I’m here for the horse,” he says. “To help him get a better deal.” He and his mentor, Tom Dorrance, were the first to promote looking at a relationship with the horse from the horse’s viewpoint. Mariah’s owner wasn’t willing to do that. His question would likely be: What’s in it for me? Rather than, What’s in it for the horse?

Perspective is everything, I was discovering. And I wanted desperately to change the perspective of the old cowboy. But what did I know? I was a newbie. A novice. Why would the cowboy or anyone else listen? I felt so helpless.

It would get worse.

As Kathleen dismounted, I looked deeply into this horse’s eyes. I rubbed her, and the closer I got, the more she would turn her head, or step away. I tried to get her to sniff my hand, or my nose. That’s what horses do when they greet each other. Sniff noses. All six of ours now go straight for the nose when we approach. Blow a little, sniff a little. And we return the greeting. Much nicer than the way dogs greet each other.

I reached out one last time to rub Mariah on the face, and she pulled away. Just enough. I turned to leave and quite without warning she stretched out and nuzzled my hand. Well, maybe it was more of a bump than a nuzzle. But as I turned back to look at her, it became very clear to me that this cute little mare had received everything I had given, she just had no clue what to do with it. Trust had never been part of her experience with humans.

On the ride home, I asked Kathleen, “So… what did you think?”

“No,” she said flatly.

The silence telegraphed my surprise.

It seems that during her ride Mariah had spooked a couple of times at the dogs barking on the far side of the arena. That, plus the lack of any kind of warmth, had done it for her. Her blink, her first impression, was no.

Two weeks before she had been right on the money. I was all wrapped up in a palomino because he was gorgeous, but I was overlooking at least forty-six shortcomings.

“What don’t you like?” I had queried.

“Why would you even ask?” she said. And she was right. It was the wrong horse for us.

Kathleen and I had a deal. We would buy no horse that we didn’t agree on.

But Mariah was different. I had finally seen a tiny light in the window. Until later I would have no idea how much she had been saying with that one little bump of my hand. How much of a call it was to take her away. Away from the cowboy.

I told Kathleen about the smidgen of connection, trying to open her mind, but it was locked tight. I felt depressed. I was certain this little mare, given the choice of Join-Up, along with time and good treatment, would come around. She would begin to understand what trust was all about. But I dropped the subject and it was very quiet on the long road home.

The next morning as we sat with our cappuccino looking out over the horse stalls, I brought up the subject again The next morning as well. And the next. I was haunted by that vacant look in Mariah’s eyes, and the little bump of my hand. A cry for help. Which I believe to this day it was, but probably not as passionate a plea as I was portraying to Kathleen.

Finally, I’m sure just to shut me up, Kathleen said, “If you really feel that strongly about her, go ahead and get her.”

She arrived the next day.

I was excited and anxious to get started, confident that the sincerity of my desire and my extensive working knowledge of the Join-Up concept – approaching a full month now – would win this cute little mare over immediately. I took her straight to the round pen.

No deal.

It didn’t work.

She ran around and around, just as she had done the day we met. But no signals of any kind were forthcoming. After several minutes, she clearly wanted to stop, but she had not given me an ear. No licking and chewing. Nothing. So I kept her moving, wondering what I might be doing wrong. Perhaps she didn’t know the language of the herd. Maybe she had never known a herd.

Doesn’t matter, I objected. She’s a horse, with fifty-two million years of genetics. It’s in there somewhere. Has to be. I was beginning to reel with dizziness as Mariah continued to run circles around me. Finally, I gave up, put her in a stall, and retreated to the house to watch Monty’s Join-Up DVD again.

I watched it twice.

If I was making a mistake, I couldn’t find it.

Maybe Kathleen had been right. Maybe we shouldn’t have purchased her.

Maybe she’d had so much bad treatment that she simply couldn’t respond to anything else.

Think persistence, I kept telling myself, remembering the story of an Aborigine tribe in Australia who boasted of a perfect record when it came to rain-making. They never failed to make rain. When asked how they managed to accomplish such a feat, the king simply smiled and said, “We just don’t quit until it rains.”

Back to the round pen, and more circles.

Two days of circles! Still no rain. I was determined that she was going to figure this out. But I was also becoming more and more convinced that she might very well have never been exposed to a herd; perhaps one of those horses who had spent her entire life in a stall, with no need for her native language. No opportunity to communicate with horses, and no desire to communicate with people like our friend, the cowboy.

Finally, on the third day, there was a breakthrough. Something clicked. After eight or nine trips around the round pen, her inside ear turned and locked on me. Then came the licking and chewing. Soon her head dropped and she began to ease closer. I let her stop, turned my back, and lowered my shoulders. Nothing happened for several minutes and I was about to send her off again when suddenly she walked up to me and stood, nose to shoulder. No sniffing, like Cash had done. But at least she had touched me. Of her own choice. And now she was just standing, instinct in control, but with no apparent understanding as to why.

It was enough. I was grinning from ear to ear.

I turned and rubbed her forehead and this time she didn’t pull away. As I walked across the pen, she followed, right off my shoulder, making every turn I made. I gave her a good rubbing all over. Belly, back, hindquarters, everywhere. And I blew in her nose, and sniffed. She didn’t respond, but she didn’t move away either. I could almost see the wheels turning. Do I know this greeting? Why’s he doing that? I don’t hate it really, but I’m not sure what it means. It does seem familiar.

Somewhere, deep down in her brain, her genetics were finally bubbling to the surface, freed at last from the perspective of the old cowboy.

The next morning when I went down to the stables to feed and muck, I realized for the first time how completely the Join-Up process had transformed Mariah. She was a different horse, waiting by her stall gate, head stretched toward me, and she didn’t move until I came over and gave her a sniff and a rub. A scratch under her jaw at the bend of the neck was her favorite. It became ritual. Every morning. And I dared not ignore her or she would scold me with a soft whinny or a snort. And then pull away when I finally came over, just for a moment, to let me know I had been naughty.

The simple act of giving her the choice of whether or not to be with me, of viewing all of her issues from her perspective, not from mine, had changed everything.

The new Mariah is as affectionate as Cash, as willing and giving, as anxious to see us… and until Skeeter came along she was Kathleen’s favorite.

I can’t help but wonder what the old cowboy would think if he knew that Mariah had learned what it means to trust.

Copyright Joe Camp

Chapter 1 and 3 Photos Copyright Pete and Ivy Ramey

Chapter 2 and 4 Photos Copyright Kathleen Camp

Order The Soul of a Horse from

Amazon & Kindle

Personally Inscribed Copies

Be sure to list the names for each inscription in the “instructions to Seller” field as you check out!

Watch The Soul of a Horse Book Trailer

——

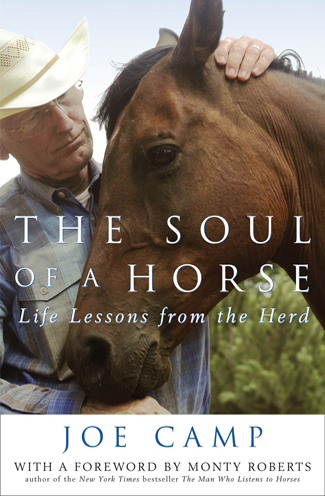

The story of our journey with horses (to date) is told in the two books that follow: the national best seller The Soul of a Horse – Life Lessons from the Herd and its sequel Born Wild – The Soul of a Horse.

And what a story it is as two novices without a clue stumble and bumble their way through the learning process so that hopefully you won’t have to. If you haven’t read both of these books already please do because with that reading, I believe, will come not just the knowledge of discovery but the passion and the excitement to cause you to commit to your journey with horses, to do for the horse without waiver so that your relationship and experience will be with loving, happy and healthy horses who are willing partners and who never stop trying for you. Horses like ours.

The highly acclaimed best selling sequel to the National Best Seller

The Soul of a Horse – Life Lessons from the Herd

#1 Amazon Best Seller

#1 Amazon “Hot New Releases”

Amazon & Kindle

Order Personally Inscribed Copies of Born Wild

Order Both The Soul of a Horse & Born Wild – Save 20%

Both Personally Inscribed

Please list the names for each inscription in the “instructions to Seller” field as you check out!

Read More About Born Wild

Read More About The Soul of a Horse

Watch The Soul of a Horse Trailer

Watch the Born Wild Trailer

But first read the National Best Seller that started it all: